One of the funny things about writing educational books is that, once published, each book stays a snapshot in time. The same is not true for the author though; the author continues to experiment and evolve, to try new things and grow in philosophy and practice. That is why over the next few weeks I plan to do a mini-series on the powerful lessons about giving better and faster feedback that I’ve learned since writing Flash Feedback. The core of what I do is still the same as it is in Flash Feedback, but as a little mid-winter gift, I’m so excited to share some new lessons about efficiency and effectiveness I’ve learned since I hit send on the manuscript.

Today’s topic is Feedback Literacy, which is a term coined by Paul Sutton, and it plays a prominent role in my approach to feedback these days. The core of the concept is that we often put a tremendous amount of time and energy into providing feedback and then spend almost no time and energy making sure students read, use, and understand the feedback. I’ve come to think about it like a marathoner who runs 26 miles and then walks off the course, not realizing that the race is actually 26.2 miles.

And similar to not crossing the finish line of a marathon, when we embark on the Herculean task of responding to a massive pile of student work and then aren’t clear about what students should do with it, we likely won’t get the results we want because many students might not accurately understand what feedback is, know how to use it, and/or even be interested in hearing it.

Feedback Literacy is about taking that last step and preparing students to receive and use the feedback. My approach to it continues to evolve, but here is what it looks like in my classes right now:

Step #1: We Do the Math (and Discuss the Value)

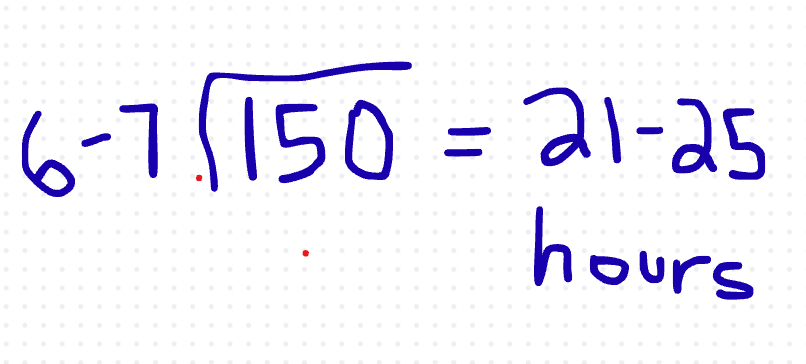

In yesterday’s setup post, I did the math behind why feedback can be such an oppressive weight upon teachers. We teachers know this math well because we live it, but most students probably haven’t thought about it. So before I provide feedback to papers, I now do the same math with students. When students walk in, I put the number of students I have in all of my classes on the board and divide it by how many papers I can read and respond to in an hour.

As the sheer size of the job of responding to papers becomes clear to students, one of them will inevitably voice the question before I even have to ask it: Why do teachers do that to themselves?

I wait for this moment and turn the question back to them, asking why those comments in the margins of their papers are worth a massive time commitment. The students always come to it quickly once I shine some light upon it: Feedback is one of the most powerful teaching tools we have because it offers a rare personal moment in the middle of the mass broadcastingthat students encounter most of the day. It provides students, in the words of John Hattie, “just in time, just for you” information individually tailored to help them get to the next level.

Step #2: The Students Start the Conversation

The opening discussion about the math of feedback is meant to plant a seed—a seed of its value and importance that ideally germinates during the next step: Having students talk first in feedback.

I’ve written before about how having students talk first in many places in our classes can be a powerful tool for effectiveness and efficiency. What talking first means in regards to feedback is that when students submit larger works for feedback, they first write notes to me about the following:

- How they are feeling about the piece

- What they see as its biggest strengths

- What their biggest questions are concerning how to improve

Giving students the chance to talk first on bigger papers/projects is helpful for many reasons: Reflection is a powerful teaching tool, it encourages viewing the drafting of a paper/project as a collaborative endeavor, and seeing a student’s perspectives on a paper/project can be very helpful for calibrating our feedback. But the primary purpose is that when students start the conversation, it reinforces the idea that feedback is not chastisement—as many feel it is—for mistakes made. It is not meant to make them feel bad. Instead it is an exciting thing because it is individual information about how the student can elevate to the next level, regardless of where they are right now.

Step #3: I Often Use Exclamation Marks and Even Emojis

I have a quick confession: Even after writing a book about feedback and speaking on it hundreds of times at this point, I’m often not great at receiving it. When an editor offers me notes and suggestions, I often find myself growing grouchy and irritable. The irony of someone who wrote a book on feedback growing annoyed when offered feedback is not lost on me, but I think it also speaks to something important. Feedback is hard to hear for nearly all of us, even when we know better.

A truth that we teachers often forget is that feedback lifts a mirror to areas of struggle and the gaps in thinking, and it generally isn’t easy to gaze at those things. That is why I now regularly use exclamation points and even emojis when I respond to student work (when you highlight something on Google Docs, the option to add emojis is right there). I got this idea from (fan) fiction sites, which are full of emojis and exclamation points alongside meaningful feedback. When students first showed me these sites, I was struck by how the effusive, emotive tones of the reviewers often largely de-fanged the defensive reactions that regularly come with critiques. These little slices of text-speak might not fit the style for every teacher, and I don’t use them for all students or in all situations, but I have found them to be a useful tool for the times I want my feedback to feel less confrontational and more conversational.

Step #4: All Feedback Comes With Guidance

Every piece of feedback I provide now comes with an explanation of how to use it. For smaller assignments, I generally allow students another crack at whatever went wrong, so they can use the feedback to work towards mastery:

For larger assignments, students are required to follow a process that is discussed in my final step.

Step #5: We Come Up With a Game Plan for Feedback in Small Conferences

I once read a study that found that 51% of students in a university class misunderstood what the teacher meant by the word analysis—which is a word I’m assuming most instructors didn’t think twice about using. I share this because it helps me to remember that the only thing we can assume when it comes to our feedback is that regardless of how carefully we construct it, some of it—much of it most likely—will be misconstrued.

This is why conferring over feedback is critical. When we sit and talk with students, we can identify the points of confusion and make sure the path forward is clear. Of course, the rub is that conferring comes with similar logistical issues to providing feedback. My biggest class is 32 students and my class periods are 57 minutes. That means I can provide about 1.5 minutes of feedback per student per class. And since I only have two days of drafting after I provide feedback, that means I need to conference with students in three minutes or less.

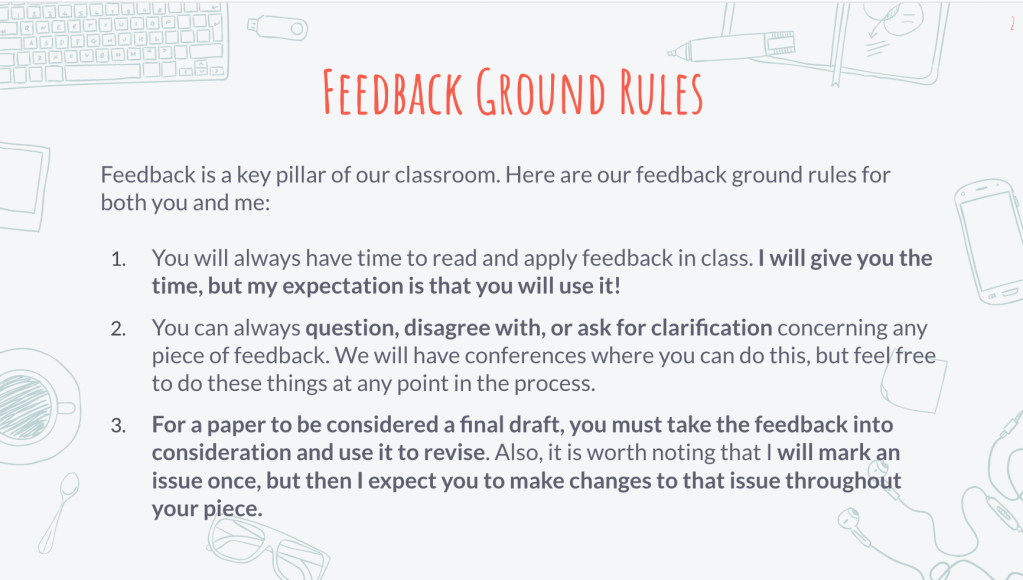

To do this, when students receive feedback, they fill out a Google Form that asks them to read and respond to my feedback (see here for a copy). The form acts as the foundation of our conference and helps to ensure that we conference as quickly as possible because it means I’ve read their papers, they’ve read my feedback, and we are ready to hit the ground running. I also give students these rules for using the feedback, which sit at the front of the room as they draft:

In the end, here is how I think about Feedback Literacy: We teachers tend to have clear policies about dozens of things when it comes to big papers and projects. We clearly state our preferred font size, page length, and spacing; tell students exactly how to format headings and quotes; and lay out numerous other criteria. So shouldn’t we be equally as clear about our expectations concerning the thing that we spent 20 hours providing that can also supercharge student learning? I hope this helps you to do that!

Yours in Teaching,

Matt

If you liked this…

Join my mailing list and you will receive a thoughtful post about finding balance and success as a writing teacher each week along with exciting subscriber-only content. Also, as an additional thank you for signing up, you will also receive a short ebook on how to cut feedback time without cutting feedback quality that is adapted from my book Flash Feedback: Responding to Student Writing Better and Faster – Without Burning Out from Corwin Literacy.

Leave a comment