When I speak to teachers about feedback, I often open by asking my audience the following question:

How many of you meaningfully discussed how to give feedback while training to become a teacher?

Generally few, if any, hands go into the air, which instead tends to slowly fill with awkward laughter as everyone begins to realize a rather absurd truth: We spend a huge amount of our teaching life responding to student work, and yet most of us received little or no instruction concerning how to do that while in school.

This question then naturally leads to another question:

Given the vacuum of guidance concerning feedback best practices in many teacher training programs, where do teachers learn how to give feedback?

For the answer to this, I’ll turn it over to Nancy Sommers, who in her 1982 essay “Responding to Student Writing,” points out that, in the absence of other options, most teachers ultimately mimic the approaches to feedback their favorite teachers engaged in while they were in school.

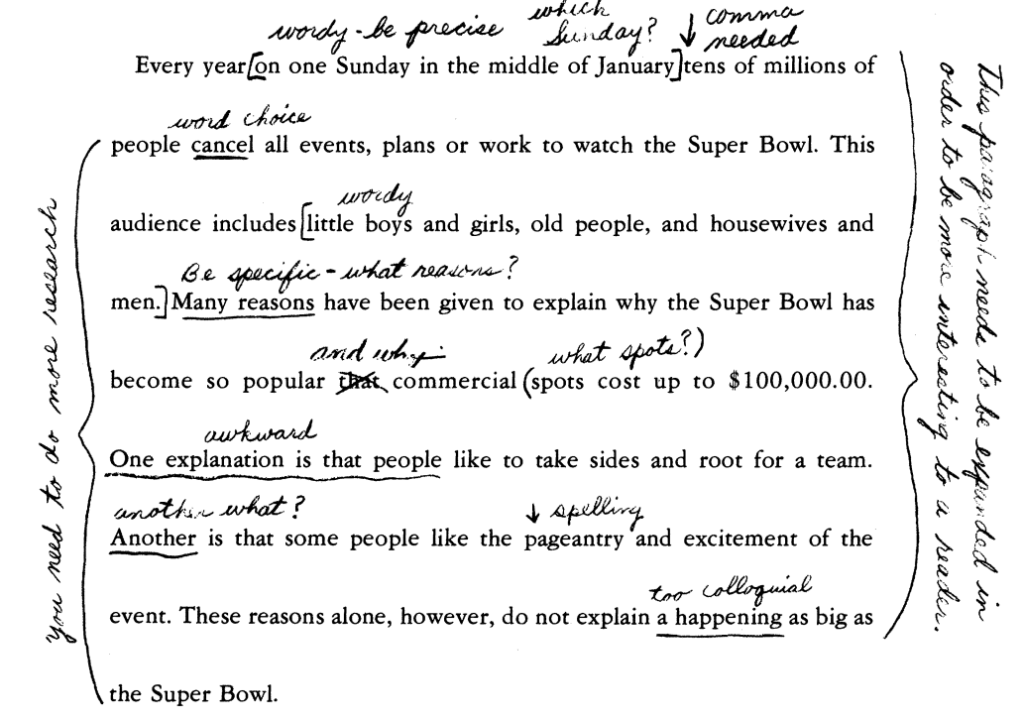

Summers calls this method of passing on feedback practices “the Unwritten Canon” and noted that over time, the Unwritten Canon has led to some common approaches for responding to student work that seem reasonable at first and yet are less than ideal when you look under the hood. Two of the most common, which she demonstrates with the sample paper on the right, are the following:

- The job of a teacher is to collect and correct student work by pointing out all the errors and issues, much like an editor would.

- The teacher generally delivers the feedback via terse comments snaking in and out of the margins.

Even 42 years after Summers’ essay, this approach to feedback likely feels familiar to you, and as a young teacher, my feedback looked exactly like the feedback in Summers’ example. To my credit and the credit of all those whose papers look like that, I believe there is a good reason for the Unwritten Canon’s existence and persistence: In the moment, it makes everyone feel good. When students see that a teacher has thoroughly marked up their paper, they know they’ve been seen—and students feeling seen is a powerful and important thing. And when a teacher points out and fixes every error in a paper, the paper generally gets way better because the students know exactly where the errors are and how to fix them.

The problem with the Unwritten Canon is not that it doesn’t do any good whatsoever; it is that it is neither as effective or efficient as some other practices when it comes to long-term student learning. For the reasons why, let’s think about how we learn:

- We can generally only learn one new complex skill at a time

- We generally only learn when we—not someone else—are the one putting in most of the work.

- We generally need to revisit and think hard about something multiple times for the lesson to stick.

The Unwritten Canon generally doesn’t follow these best practices. Students instead have dozens of different topics thrown at them (Summers’ example has at least nine distinctly different topics), the teacher does most of the work, and students are rarely put in a position to think hard about the feedback or revisit it numerous times. Nor does this approach include laying out a clear path forward for students to travel, which feedback research puts as being an essential piece of effective feedback.

And the results of this are well known and often griped about: The sheer time required to mark every error on every paper pushes many teachers (including me at one point) into burnout, while the lessons jammed into the margins of student papers seem to regularly wash away from student memory like chalk after a rainstorm.

Of course, many teachers know that the tried-and-not-as-true-as-we’d-like methods of the Unwritten Canon can be inefficient and ineffective, but to return to the start, the problem for many remains that many of us have never been taught any alternatives.

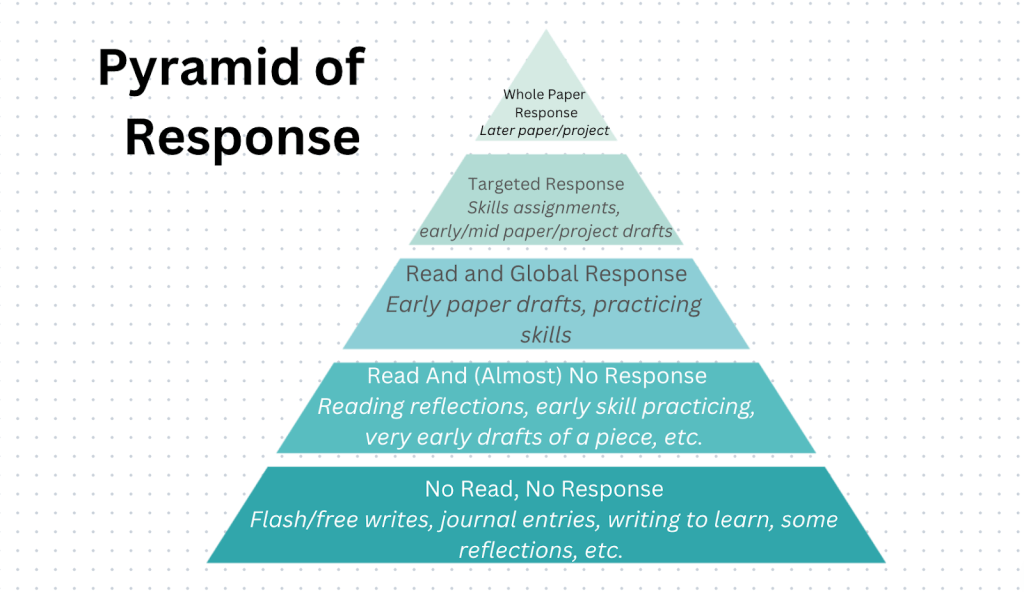

That problem is why I’m particularly excited about today’s topic, The Pyramid of Response. It is the core of my answer to the problem of the Unwritten Canon, and while Flash Feedback has an earlier version of this (the Pyramid of Writing Priorities), I wanted to share how my pyramid looks now. Here it is:

Two anchoring ideas at the core of the the pyramid are the following:

- We don’t write or create in the classroom for one reason. Sometimes we are practicing, sometimes we are exploring, and sometimes we are showing what we know. Thus our responses (or purposeful non-responses) to a piece of writing/work should depend on the purpose of the writing/work.

- We must be incredibly thoughtful about when and how we respond to student work because our time is very, very limited, making it very, very valuable.

The Pyramid of Response prompts me to think through these two considerations and then select the response that best fits the student work. Let’s take a moment to look at some of its key parts:

No Read, No Response

The bottom rung of the pyramid serves as a reminder of a point that research has made quite clear: Students should be writing and creating far more text and content than we could ever read or look at, let alone respond to (Most research I’ve seen puts the ideal amount of daily writing at 30-60 minutes per day). Coaches and music teachers have known this all along. They will show an athlete, actor, or artist a skill; offer a few pointers; and then give the student time and space to engage in the messy, often embarrassing work of getting comfortable with the new information or skill. They don’t need to watch every note played or ball kicked for learning to happen—in fact stepping back and allowing plenty of practice before feedback is often the most effective and efficient approach for both student and teacher.

So anytime students write or practice something, our first question needs to be whether it is worth spending some of our extremely limited time reading and/or responding to it. My general rule is that if the students are doing something to practice a new skill, consolidate their thinking, explore, or otherwise reflect, it might be worth setting the pen down.

Read and (Almost) No Response

Formative assessment—where we quickly take the pulse of student learning—is essential to understand what is going on in the classroom. But not all formative assessments require a response. Even still, there is the long tradition where teachers mark up any assignment that crosses their desk or desktop to demonstrate that they were there.

The problem with this approach is that even the shortest comments cost meaningful time and cognitive load when taken at the scale of all of our students. The second rung of the pyramid is a reminder that just because we read something as a formative assessment, we don’t necessarily have to respond to it.

To figure out if something is in the second rung, think about whether a response is worth the hours it will take—whether it will move the needle in student learning enough to justify the time spent.

For me, the biggest issue with the concept of reading and not responding is that, even though I know that it is sometimes a best practice, I still feel the pressure from the Unwritten Canon to mark the paper to show that I actually read it. What I do now is that when I read student work as a formative assessment, I keep a notebook next to me. As I read, I jot down five or six favorite exemplars to share and celebrate with the class before my next lesson. I’ve found that this makes the same point—I read your work thoughtfully—and acts as a form of retrieval practice and extra opportunity to bring a bit of joy and celebration into my classes.

Read and Global Response

As a new teacher, I distinctly remember discussing something (let’s say topic sentences), and then when students wrote their essays, I would grow frustrated as I found myself spending hours reexplaining what a topic sentence to seemingly every. single. paper.

Today, I still find myself in similar situations, but when I find I’m repeating or reteaching time and again, I’m now excited, not frustrated. Why? Because once an issue clearly becomes a whole-class issue, it means I can stop writing about it in margins of individual student work and instead construct a Global Response.

In Global Response, the teacher takes the most common issues and creates a whole-class response. Getting serious and organized with my global response has become a really big part of how I avoid putting dozens of comments on drafts of larger papers and projects. Here is how it works:

When I’m doing formative assessment or giving formative feedback to student work, I’m always looking for trends, big or small, and when I see them, I put them into two categories:

- Whole-Class Lessons: I use whole-class lessons for larger common issues. Often, I will wait to teach or re-teach these lessons until students are in the process of drafting a large paper or project. I will then start each lesson by mentioning that I noticed a common issue and teaching to it, followed by students taking out their papers/projects, looking for whether or not they have the issue, and working on it, if they do.

- Checklists: There are numerous smaller common issues that we notice in student work. No title, not formatting quotes right, etc.. When smaller problems pop up time and again, I put them into a checklist that students will get as they draft. This is a win-win, as once something is in the checklist, I don’t have to mention it on any more papers, and the checklist gives students more time to systematically think through the issues and learn the lessons.

This is already a lot to think on for a cold and blustery Friday morning, so I’ll pause the post and wrap up the discussion of the Pyramid of Response post next week. Thanks as always for reading, and for those of you in places with dangerous cold, stay warm and safe!

Yours in teaching,

Matt

If you liked this…

Join my mailing list and you will receive a thoughtful post about finding balance and success as a writing teacher each week along with exciting subscriber-only content. Also, as an additional thank you for signing up, you will also receive a short ebook on how to cut feedback time without cutting feedback quality that is adapted from my book Flash Feedback: Responding to Student Writing Better and Faster – Without Burning Out from Corwin Literacy.

Leave a comment