Given the recent Valentine’s Day holiday, I wanted to share a quick post on a feedback tool that I truly love: Student self-assessment

To understand my love of student self-assessment, think about the final draft of a major paper or project and the following question:

Should you provide some sort of feedback with the final grade/score you give?

This question is harder than it seems. One of the clearest conclusions in all of feedback research is that feedback given in the summative, final stage is dramatically less effective than feedback that comes in formative stages. Part of this drop in effectiveness is that students rarely look at final-draft feedback more than once or think about it for long—and thought and thoughtful revisiting are both essential for long-term learning. Further, once a grade or score is introduced, its gravitational weight shifts how teachers provide feedback (as they focus more on justifying the score than student learning) and how students receive it (the score draws most of the student’s attention, leaving feedback mostly ignored).

Given this, the answer might seem clear: Don’t provide summative feedback. The problem with this (and I’ve tried it) is that handing back a major assignment—one that the students and teacher worked on for weeks—with just score and no words feels cold and strange and like the final product doesn’t matter at all.

Thus, for a long time, my debate with final drafts was the following:

Should I use hours of my already-crunched time providing feedback that is minimally effective or skip it at the risk of coming across cold and disinterested?

This dilemma is where student self-assessment enters.

I’ve written before about my winding journey to student self-assessment and its benefits, but to put it succinctly, the practice of student self-assessment, if well used, can be deeply empowering for students and time-saving for teachers. I also want to make it clear that student self-assessment isn’t about us abdicating our essential role in assessment. Instead, it is about inviting students into the conversation concerning assessment in a way that saves our time and increases student learning and engagement because they are actually involved in the process.

With that in mind, today I wanted to share what my approach to student self-assessment looks like in my classes right now. Here are the steps:

Step #1: Building Student Belief in Their Own Expertise

One of the biggest threats to effective student self-assessment is our own competence. In many classes, the students view the teacher as the only true expert in the room. And if there is only one true expert, it tracks that many students might feel that they aren’t qualified to assess their own work, and indeed I run across this mindset often at the start of the year.

For me, the first step towards meaningful student self-assessment is to build a foundation of the students’ belief in their own expertise. In my classes I do that through…

- Carefully cultivating the students’ writing identities.

- Talking often with students about their idiolects and how they bring a voice and perspective that the world has never seen before—and how that means they instantly have a fresh, valuable perspective to contribute.

- Building the skill of assessment through regularly asking students to question and assess the authors’ choices in the works we read. This technique is called “Questioning the Author,” and it is a powerful tool for building student belief in their own competence.

- Engaging in meaningful peer response (more on this soon) to help students to refine their ability to assess.

Step #2: Co-Construct the Assessment Criteria

The notion of co-constructing rubrics with students is an idea I got nearly 15 years ago from Kelly Gallagher’s Write Like This. I loved the concept instantly, though I will admit that for years I struggled with it in practice. The problem was that I came in already knowing the rubric I wanted to use for each assignment, and so the “co-construction” of the rubric felt less like a real discussion and more like a game of Guess the Teacher’s Thoughts.

I finally solved that problem when our district adopted new ELA standards about a decade back. I liked the standards, but the language of the standards and rubrics provided weren’t always as clear to students as they could be. One day I decided to make the co-constructing of rubrics something closer to translating the district rubrics, and I instantly knew I’d found something. Jump to today, and here is what my co-construction of rubrics looks like now:

- I generally make rubrics with my students later in the unit, once we’ve read everything and written a rough draft of the assignment.

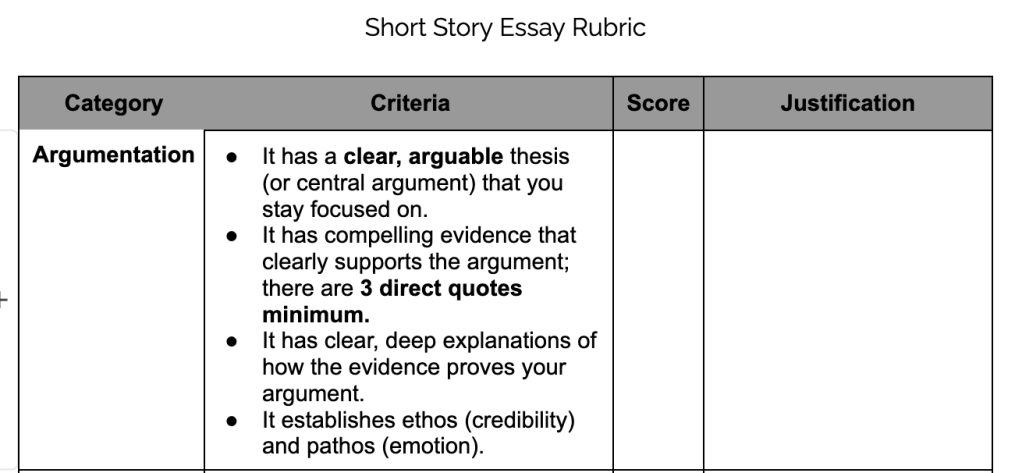

- To start the rubric creation, I show the students the district standards, and we break them into ideally three main categories. For example, here is my first essay rubric at the start:

- We then look back at all the major readings and assignments from the unit, and discuss what the criteria for each category should be.

- The last step is simply for me to polish our discussion into a rubric and give it to students.

Step #3: Model and Practice It

I’m two decades into my career, and yet I still constantly find myself assuming students will be able to do something because, well, I can do it, and I forget they aren’t me. This issue is commonly called The Curse of Knowledge, or the idea that those who can do something well often forget what it is like to not be able to do that something well, and it was a thorn in the side of my early attempts at student self-assessment because assessment was so clear to me.

To counteract the Curse of Knowledge and norm expectations, I now model for students my approach to assessment every time I ask them to do self-assessment, and I also have several practice assessment sessions with sample papers or projects. This modeling and assessment doesn’t have to add a lot of extra time either; ELA classes often share mentor texts and discuss expectations. Instead, the key is to make sure to take a few minutes to put on the lens of assessment at least a few times while looking at models and discussing expectations before asking students to self-assess their own work.

Step #4: Listen, And Then Talk

If you engage in student self-assessment, it is important to realize you are opening up a conversation. This means that you have to truly listen first, and to help me to hear and understand a student’s perspective, I ask them to write a short justification (see the last box of my rubric above) for why they gave the scores they did.

I find that if I’ve done the first three steps well, I agree with 90-95% of the students’ scores and justifications. Generally, they know exactly what their strengths and areas in need of improvement are. In these cases, a quick word from me affirming their assessment and maybe offering one last parting thought is all that is needed in terms of final feedback.

Of course, there will always be a few students who give scores I don’t agree with. That is fine. In real conversations we don’t always have to agree with the speaker. In those cases, I seek the students out and we talk about the gap between our scores and come to some conclusion. More often than not, I find students who sought to give themselves a higher score than I would give often want to revise it and do better to get those higher scores. This is an outcome I love because it stretches the learning on the assignment in a way that almost never happened when final assessments came solely from me.

I’ll be back with Part II of my Pyramid of Response early next week, but until then, have a great weekend, and thanks as always for reading!

Yours in Teaching,

Matt

If you liked this…

Join my mailing list and you will receive a thoughtful post about finding balance and success as a writing teacher each week along with exciting subscriber-only content. Also, as an additional thank you for signing up, you will also receive a short ebook on how to cut feedback time without cutting feedback quality that is adapted from my book Flash Feedback: Responding to Student Writing Better and Faster – Without Burning Out from Corwin Literacy.

Leave a comment