So far in this month focused on the essay, I’ve spoken about the power of giving students choice to pursue their own interests in essays, we’ve looked at a student perspective on the essay, and I’ve argued that the essay shouldn’t be the only genre of writing we elevate.

I wanted to end my posts concerning the essay with what has been maybe the biggest shift in my classroom this year: the more human responses I now give to essays.

Until very recently, my response to essays tended to focus on the main elements that go into making an essay–the thesis, topic sentences, evidence, analysis, and introductions/conclusions, with a few occasional discussions of mechanics or word choice. But this year I got to wondering if all or even most of our attention should go to towards those things. Here’s why…

Some of my recent writing led me to do some research on the creator of the essay, Michel de Montaigne. Montaigne (along with pretty much all early essayists) wrote essays mainly as a vehicle for self-exploration, saying to those who questioned why he would do this, “I would rather be an expert on me than on Cicero.” For him, the essay form he created was an exercise in exploring his own thoughts and trying to come to some conclusion (the original French “essais” quite literally means “to try”).

This self-focused, exploratory history of the essay got me wondering if giving responses to students that focus only on form and technical aspects can send the wrong message concerning what an essay is and what purpose it serves. I began to worry that it might quietly tell students that when it comes to an essay, deepening one’s ideas and developing one’s voice don’t matter as much as following the right rules and plugging the right widgets into the right spots. If that is indeed the message students get, no wonder so many really don’t like essays.

I do want to say before I go any further that this is not going to be an argument to not talk about technical aspects like organization, use of evidence, or the placement of the argument when giving students feedback to their essays. These things matter a great deal, and I talk about some of them in pretty much every essay I respond to.

Instead, it is an examination of the question of whether our students would benefit more from our responses to their essays if those responses were more balanced in the focus given to technical aspects and the focus given to the the person behind the essay and ideas they are grappling with in the essay.

Doing this would not only align more closely with the self-exploration Montaigne created the essay to accomplish, it all might come with the following advantages:

- Responding more to the students as people and their ideas would allow us to make a clearer case to them that we are truly listening, and strong listening has been shown to make those speaking less anxious, less defensive, more self-aware, more open to criticism and hearing alternative viewpoints, and more interested in sharing their ideas with others–all of which could benefit student essay writing.

- It is well-documented that when teachers and students have more of what are often called touch-points, which are any interactions where adults notice students and see their strengths, interests, stories, and beliefs, the students become more engaged and resilient.

- When we have a real audience, we are generally inspired to go deeper and get it right. In an Atlantic article called “How to Make Students Care About Writing,” an ex-student of a teacher named Pirette McKamey recalls how she would give him comments like, “This is so interesting. I never thought of it this way,” or “I’m so intrigued by the point you are making here. Could you tell me more what you mean by that?” This student also recalls that while he got mostly D’s and C’s before McKamey’s class, he felt compelled to respond to these comments by putting in the work, so he spent hours in the library writing essays that “Ms. McKamey [would love] more than anything she’s ever read.”

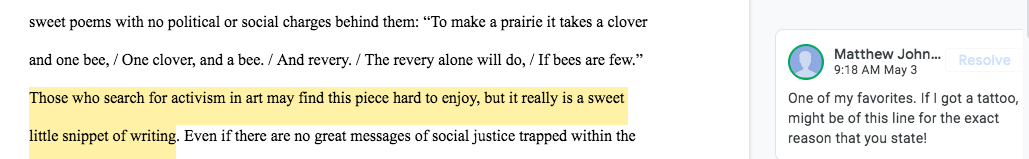

With this question in mind of whether I should take a more human response to essays, this year I tried to do more direct responding to student ideas and the students themselves when I gave them feedback to their essays. This wasn’t a serious time-investment–a comment or two here or there–and it took a lot of forms. Sometimes it was as simple as a basic affirmation of an idea or statement, like this response I gave to a student who stated that she loved the Emily Dickinson poem “To make a prairie” because it avoids diving into some deep theme and instead just revels in the simple beauty of the world.

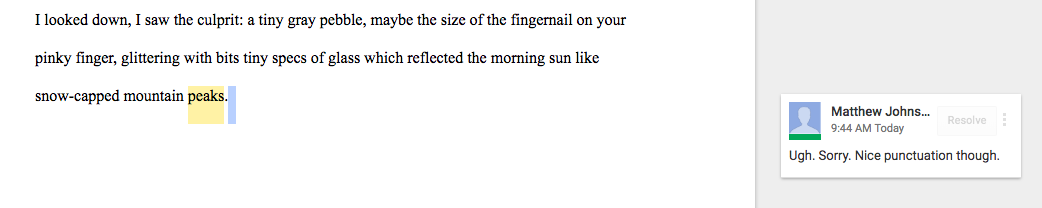

Other times it was an emotional responses to something in their paper, like my comments to this student who, in an assignment focused on using colons and semicolons, recounted breaking her phone that very morning…

Sometimes it came in the form of me asking follow-up questions to show my engagement…

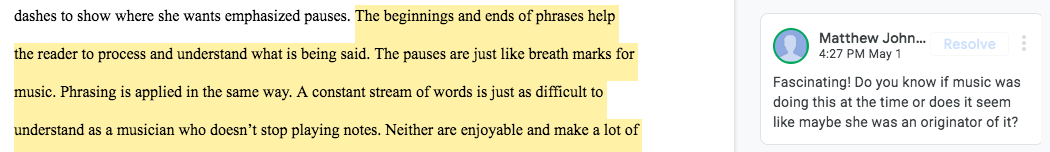

Or me adding to an interesting concept in the way we often do when we are listening closely in verbal conversation…

And at times it even resulted in me challenging student assertions in a way that showed that I was paying attention…

In the end, the data from my experiment was anecdotal, but it was also really clear. As the year rolled on and I continued to find ways to respond to my students and their ideas more directly, I noticed that their writing showed an engagement, voice, and depth that I’ve never seen before in my twelve years. And I really do think it was because I never lost sight of the fact that yes, I was responding to them as growing writers, but I was also responding to them as growing people–people who, like all of us, love to be noticed, heard, and connected with!

Yours in teaching,

Matt

Let me help you!

Teachers are busy–too busy–so we need to share with each other. That is why this blog exists. I’ve studied and written about writing instruction for over ten years and would love to share what I’ve found with you. Join my mailing list now and I will send you a thoughtful post about teaching writing each week. As a thank you, you will also receive a copy of my free ebook A Game of Inches: Making the most of your feedback to student writing and deals on my upcoming book from Corwin Literacy on best practices in writing instruction.

Leave a comment