I was at the National Council of Teachers of English conference* a couple weeks ago, and as I walked through the showroom I heard the pitch from edu-AI companies, over and over and over again:

“Save time by providing instant feedback to your students.”

As a full-time teacher with nearly 150 students, it isn’t too hard to figure out why companies would lead with this pitch: As I’ve discussed in this newsletter for nearly a decade, the logistics of providing feedback are nearly nonsensical for the modern teacher. Multiply my 150 students by the length of an essay/narrative (about 3 pages on average in my classes) and the result is that reading and responding to one batch of essays one time is the equivalent of reading a novel the length of Moby Dick or The Grapes of Wrath and providing thoughtful feedback to every single page.

And it isn’t like my students only do one paper or project either. There are dozens of smaller or medium length assignments each quarter that also require feedback and/or assessment, and every one of those takes another 2.5 hours for every minute it takes me to read, respond, and/or assess per assignment.

Also, did I mention that my sole prep (which also acts as the only protected time I have to plan lessons, write emails, and chop away at my endless to-do list) is 57 minutes?

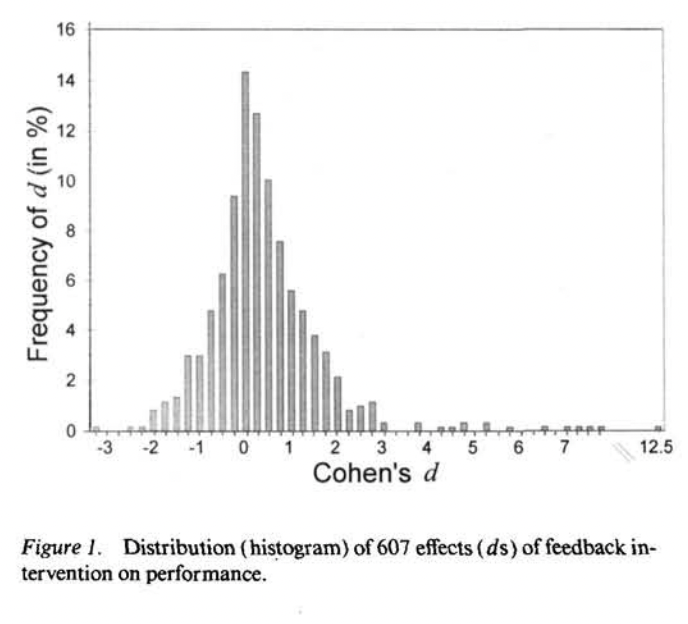

It doesn’t take a math teacher to figure out that the problem of time above is a fraught one. Making matters even worse is this graph, which I’ve been thinking and worrying about over the last few years:

This is from Kluger and DeNisi’s “The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance,” which is a large meta-analysis of 607 studies on feedback. The graph essentially shows how feedback in various studies impacted student performance, and for me two things stand out. The first is that the biggest spike is over zero, meaning that the most likely effect size of feedback is nothing, likely because the feedback wasn’t read or thought about long enough to lead to meaningful learning.

The second is that roughly ⅓ of the effect sizes are negative, meaning that about a third of feedback given by teachers made student performance worse.

If one puts together the fact that Kluger and DeNisi found roughly half of feedback has no effect or a negative effect with the absurd amount of time it takes for teachers to provide feedback, the end result is truly heartbreaking. It is heartbreaking for teachers, who sacrifice not just their prep periods but their nights, weekends, and many waking moments in between providing feedback that in many cases has no or even a negative effect on student learning. It is also heartbreaking for their students, who miss out on the huge learning bump that can come when feedback is used well (Another bigger and more modern meta study—John Hattie’s ongoing effect size list—identifies well-done feedback as one of the most effective things we can do to help our students grow).

In the end, the demands and uneven impact of feedback brings us back to the question posed at the start: Is the solution to this problem Gen AI and letting it do the heavy lifting in providing feedback? The answer to this, for reasons I’ll get into over the next few weeks, is for me a pretty clear no. The tough reality is that there remains no instant automatic easy button that will solve this problem. There is no silver bullet. But as my friend Dave Stuart Jr. likes to say, while there are no silver bullets, there are swords—swords that can slice off inefficiencies and add up to meaningful change. There are also best practices to make our feedback more powerful.

As a sort of December gift to subscribers, my plan over the next few weeks is to share my keys, as of 2025, for what we can do to cut down the hours we spend on feedback while also ensuring that the hours we do devote get the results we want. I also plan to focus on the lessons I’ve learned since publishing my book Flash Feedback in 2020. Think of this mini-series as a just-for-subscribers second edition of sorts that will start tomorrow with feedback literacy and end with what the most recent research says about how to think about that “instant” Gen AI feedback.

Look for a post tomorrow on one of my all-time favorite subjects, Feedback Literacy, and if you have any specific feedback questions or concerns, please let me know and I’ll try to work them in as well!

Yours in Teaching,

Matt

*Proposals for the 2026 NCTE in Philadelphia are open now; the best sessions generally come from folks who are in the trenches, so you should think about it!

If you liked this…

Join my mailing list and you will receive a thoughtful post about finding balance and success as a writing teacher each week along with exciting subscriber-only content. Also, as an additional thank you for signing up, you will also receive a short ebook on how to cut feedback time without cutting feedback quality that is adapted from my book Flash Feedback: Responding to Student Writing Better and Faster – Without Burning Out from Corwin Literacy.

Leave a reply to Better, Faster Feedback Part 1: Feedback Literacy Revisited – Matthew M. Johnson Cancel reply